Article: Part 1 - The man: from the city to the mountains

Part 1 - The man: from the city to the mountains

Published on 12/08/2022

Antonio, known by all as Toni, Gobbi was born on 18th June 1914 in Pavia, in the heart of the Po Valley.

Exactly ten days later, on June 28th, in Sarajevo (about 1000 km from Pavia), the Serbian nationalist student Gavrilo Princip shoots and kills the archduke and heir to the throne of Austria-Hungary Franz Ferdinand, effectively triggering the First War world: the world will never be the same again.

Antonio was born into an upper middle class family and is the eldest son of Gioachino Gobbi, a lawyer, and Pierina Oliva, a housewife, both from Emilia. The craft of the law is in the family tradition. The couple will have three other children: Rita (1916-2011), Giuseppe (1920-2005) and Marilena (born many years later, in 1931). With his sister Marilena, now 91, Antonio develops a very strong bond that will last a lifetime. "One of my earliest childhood memories is on the strong shoulders of my big brother" remembers Marilena "It was a mid-August of many years ago. I still see the departure at 3 in the morning, with the whole family. I was little, Toni must have been 18 years old. I had his strong hands around my ankles and I felt proud and confident ”.

With his sister Marilena, now 91, Antonio develops a very strong bond that will last a lifetime. "One of my earliest childhood memories is on the strong shoulders of my big brother" remembers Marilena "It was a mid-August of many years ago. I still see the departure at 3 in the morning, with the whole family. I was little, Toni must have been 18 years old. I had his strong hands around my ankles and I felt proud and confident ”.

The trip her sister tells about was simple, a ritual for many people from Vicenza on the day of the Assumption: they all went up together to the top of Mount Summano, still dominated today by a large concrete cross. “I remember his rhythmic step, always the same,” says Marilena. “I remember the way he put the backpack on his back and then the recommendations: stay straight, don't put your hands on my head, I'll hold you. Toni was the one who understood me, and he always treated me like a daughter. I miss him, even today when I am now old and many, many years have passed."

When Antonio turns 8, the family moves to Vicenza. He is a very energetic kid and also an excellent student, in short, he is gifted both in school and outside of it. A friend remembers him playing alone, in the inner courtyard of his building, challenging imaginary friends and dribbling air opponents until he meets the goal mirror. With his hair tousled, he exudes energy and confidence in his solitude because, as he would have explained as an adult: “A man that is respected must soon learn to be alone. Maybe we need to start when we are young, if we don't want to end up in anonymity; and then look into the folds of our misery. Because in serious moments, when life depends on the strength and serenity of our solitude, only then can you evaluate it ".

It was precisely in those adolescent years that Antonio began to be called Toni, as often happens in Veneto. And Toni will be for the rest of his life. "Even the Great Saint of Padua, if born in our day, would call himself Toni!" he will tell friends.

In 1934 my grandfather graduates from the Tito Livio high school in Padua and, following in his father's footsteps, he enrolls in the faculty of law. It is in the 1930s that Toni begins to discover the mountains, which beyond a few walks and some summer holidays, is not in the tradition of the Gobbi family. The Vicenza of those years is a hotbed of mountaineers, and Toni begins attending the “Giovane Montagna” group, a Catholic-style association, thus discovering climbing, skiing and also mountain running.

The departure from home often takes place by bicycle, because those are, in the words of his friend, writer and mountaineer Gianni Pieropan, “the years of cycle-ski-mountaineering”. At the time it was actually an almost obligatory choice, because few own a car and without it just getting close to the mountains is a real adventure.

“Dad always worried when he left for the mountains. Our mother let him go and didn't say anything, but inside her she kept a storm of images capable of quieting down only when he returned,” remembers Marilena. “After all, how can you prevent a lover from pursuing his passion? It would be like locking him in a cage”. The Gobbi family soon realized that this would not be the right path.

Toni knows of the restlessness and fear in which he leaves his family when he goes to the mountains. "I jump out of bed and open the window," he writes in a story dating back to June 1932. "On the horizon I notice an imperceptible strip of morning light. I go out, get on my bike and take a last look at the house. As I go towards the gate, I hear a window open, it is my mother who got up to see me leave, trying not to be seen. She doesn't want me to understand her concern for her. Now, in the dark, she will draw a sign of the cross to bless me and pray to the lord that nothing serious happens to me. I would like to go back to her, throw myself into her arms and kiss her. Tell her all the good I want her and apologize if I make her feel anxious. I would stop if she asked me in her dear voice. I take another look at the increasingly clear and distinct mountains, attracted by their irresistible charm, I pedal at breakneck speed towards happiness ”.

At the end of the 1930s, after years of activity with friends from Vicenza, Toni's approach to mountaineering evolves into a more individualistic dimension, with the aim of raising his technical level and maybe even making it a profession.

It is the twentieth century with its intense history that gets in the way of his projects.

After graduation, having ended the postponements granted for study reasons, Toni is called to arms and on August 31st, 1939 he enters the School of Officials of Bassano del Grappa, infantry weapon, alpine specialties. The next day, September 1st, Germany invades Poland, triggering the Second World War.

On April 18th, 1940 my grandfather is assigned to the Military School of Mountaineering in Aosta, with the rank of second lieutenant, as a mountaineering instructor. On 10th June 1940, Benito Mussolini announces Italy’s entry into the war. The next day Toni is mobilized at the "Mont Blanc" Battalion with the aim of defending the borders. On August 31st, the mobilization ceases, and he returns to the school. In those years Toni's activity is divided between the military profession (he is promoted to lieutenant in 1942), mountaineering (very intense activity in 1942 and 1943) and the search for a way to follow up on university studies (in November 1940 he begins the notary practice at the office of the Ollietti notary in Aosta).

The great peaks of the Western Alps fascinate Toni, but it is a beautiful blonde girl who conquers him.

Romilda Bertholier, seven years younger than him, is an elementary school teacher, enrolled at the University of Turin, faculty of Letters. The mountain is in the family tradition: Romilda is the daughter of a mountain guide (Prospero Bertholier, 1887-1976) and the sister of Elvira who is married to the Courmayeur guide François Thomasset. In addition, Prospero and his wife manage the Pavillon refuge, an important crossing point for mountaineers heading to Mont Blanc in the 1920s and 1930s. The Mont Blanc cable car (now Skyway Monte Bianco), of which the Pavillon is the intermediate stop, will only be inaugurated in 1947.

On 8th September 1943, once again fate got in the way, with the radio announcement of Marshal Pietro Badoglio. “The Italian government, having recognized the impossibility of continuing the unequal fight against the overwhelming opposing power, in order to spare the nation from further and more serious disasters, has requested an armistice from General Eisenhower, commander-in-chief of the Anglo-American allied forces. The request was accepted. Consequently, any act of hostility against the Anglo-American forces must cease by the Italian forces everywhere. However, they will react to any attacks from any other source ”.

With the armistice, almost everyone is looking for a way to return to their previous life, but not Toni. He chooses to remain at the foot of Mont Blanc and to marry Romilda on October 18th, 1943.

They will live a sweet and intense love story for a lifetime, as many letters testify. The union is cemented by the mountain, a great passion of both. Two children were born from their union: Gioachino in 1945 and Maria Barbara in 1949.

These are difficult years, but Toni has everything he needs to feel good: mountains, love and understanding. He begins to think that Courmayeur could become his final home. The village is full of displaced people and jobs have to be invented. Toni and Romilda try to invent themselves as teachers of a home high school. He teaches Latin, Greek and Italian; she teaches French and philosophy.

In November 1943 my grandfather Toni enrolls again at the University of Padua, Faculty of Letters, aiming for a second degree that he will not achieve but which testifies to a passion. Her sister Marilena still remembers Julius Caesar's "De Bello Gallico", which Toni had made her learn by heart! Toni will love writing all his life, and in 1950 he will even win a Saint Vincent prize for journalism.

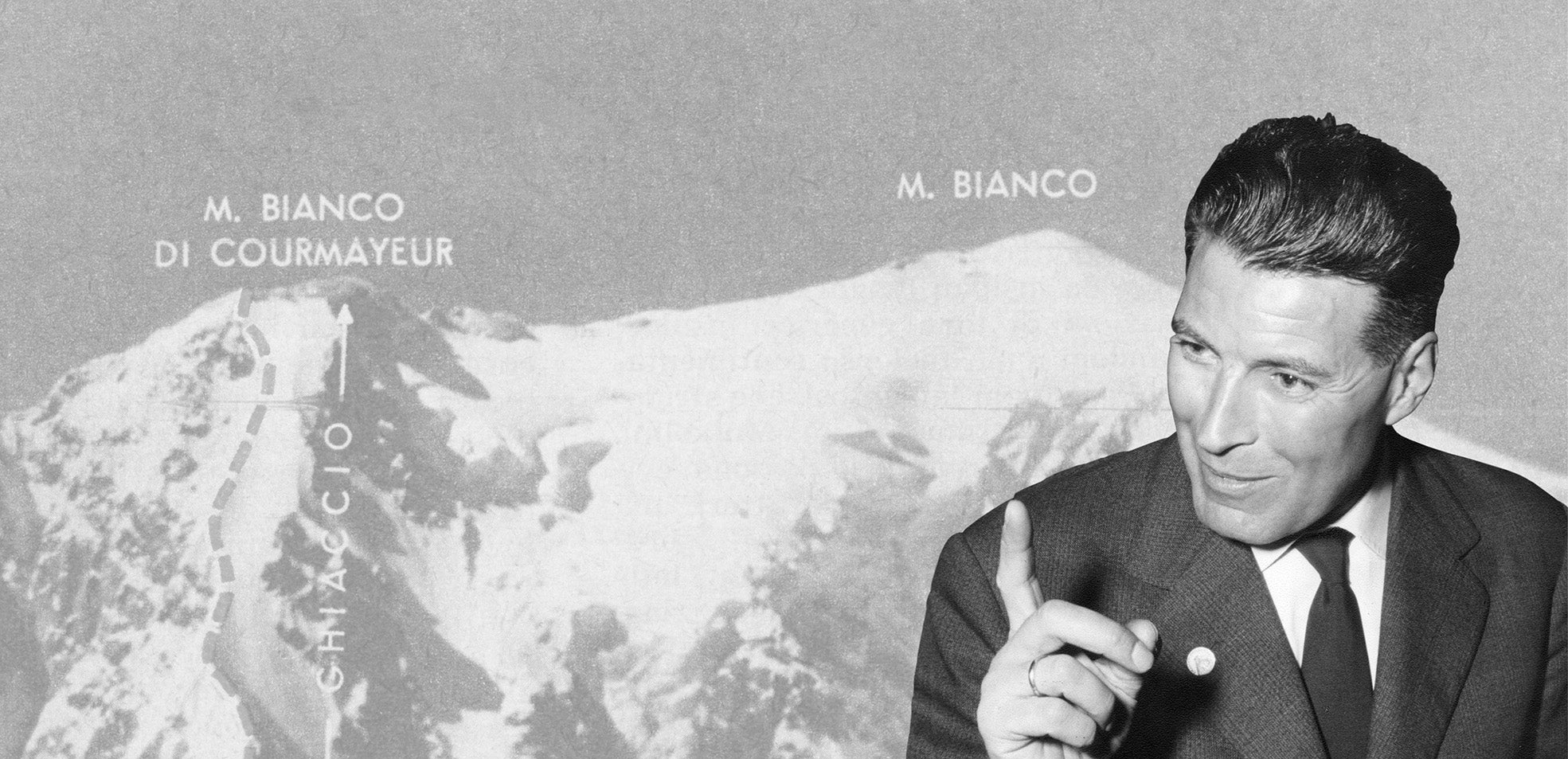

My grandfather is in fact a sophisticated city man who embraces the cause of the mountains and represents the point of contact between these two worlds, an unusual position for the time. “He was a man of great physical and psychological strength, of weight, of culture. He had a statuesque face, a pronounced jaw and sharp features, but I remember the wonderful smile that exploded in this face cut in stone. You could feel his urban origin: when he put on a jacket, the jacket suited him! And he had an important, qualified speech ”: this is how he relives in the words of Giacomo Bozzi, son of Irene Bozzi, who was one of Toni's main customers and a friend of him.

Another friend recalls: “Even with the hard edges of a strong and proud character, he was allowed to exercise an undisputed superiority on a technical and human level; it was almost impossible to escape the charm and influence that emanated from his person and not be partially subjugated by it. You could perhaps not share some of his uncompromising opinions, but you could not ignore his inimitable consistency and the seriousness that he manifested in the principles."

He often knew how to exert his influence even with just his eyes. He had light gray eyes that could become cold as ice and freeze the interlocutor: "He inspired fear but also protection. You had to do what he said, but you knew he would take care of you,” his daughter remembers. This human side also lives on in the words of his sister Marilena: “The kindness he had with me ... his eyes when they looked at me gently, they caressed me”.

Then, when it was party time, he knew how to let himself go and loved to sing, especially the mountain songs during the mountain guides' parties. In the car, then, he let himself go too much, and that's where he gave his family the greatest worries. He had learned to drive late and often had excessively fast, jittery and jerky driving!

Returning to his relationship with the world of the mountains, his path is marked even before the war is over. Toni becomes a porter in 1943 and a mountain guide in 1946. In 1948 he becomes ski teacher and mountain guide instructor.

Joining the Courmayeur Mountain Guides Association, which was founded in 1850 and is the first in Italy and the second in the world (after that of Chamonix), is more difficult than expected because the regulation requires you to be native of Courmayeur or to be owner of real estate in the village. The problem is solved with the help of his father-in-law Prospero who will give him some land.

The citizen is so well integrated that in 1950 the Association, for the celebrations of its 100th anniversary, asks Toni to deliver the speech of thanks to his colleagues.

This result is by no means taken for granted, because in the 1940s Courmayeur was still a small mountain village at the bottom of a closed valley (the Mont Blanc tunnel will open only in 1965). In a context traditionally hostile to "foreigners", Toni manages to be accepted and appreciated thanks to a respectful and delicate approach. He will later write in a letter to a friend: “Always remember that in a mountain village where you intend to settle you must always, absolutely, consider yourself as a guest; and therefore behave like a guest in someone else's house. The hosts will, at a certain moment, consider you one of them, if you have shown that you are truly worth, that you have the right respect for traditions and the right passion for the mountains. It is also useless ... to tell and magnify what you have already done; they judge justly what you do, what you did, what you will do; and all this must be done with the head even before with the technique, with the due caution-even before with exasperated courage, with the due safety even before the understandable risk ".

Ruggero Pellin, mountain guide and former President of the Courmayeur Guide Association recalls: “He came from a city and not a peasant background. He showed up in Courmayeur at a time when, during and after the war, everyone had low ears. He had the intelligence not to force our world with his presence, but at the same time he brought a breath of fresh air, with education. He knew how to stay in our environment by making himself respected. He understood that Courmayeur could offer unique opportunities, and he was able to seize them, both in mountaineering and in commerce. "

In fact, in 1948 he opened the "Alpinist and Skier's Workshop", with the "Alps bookstore" attached (probably the first bookshop dedicated to mountain literature). The Gobbi shop will become an institution throughout the Alps and a natural reference point for all mountaineers passing through Courmayeur, both for the variety and selection of products, and, above all, for the presence of Toni himself and for the possibility of discuss with him and get his advice.

Photos: Grivel archive.

Oliviero Gobbi. After a degree in physics and a master's in management, he worked for a few years as a strategic consultant in large multinationals before joining Grivel, his family business, of which he is now the owner and CEO. He loves all mountain activities, from mountaineering to ice climbing, from rock climbing to ski mountaineering, which he practices when he can. His favorite Grivel product is the one yet to be invented.

Contributors to the writing of the article: Gianluca Gasca, Marina Morpurgo, Margherita Calabi.

Go to Part 2 - The mountaineer: from the Alps to the world.

Go to Part 3 - The mountain guide: evolution of a profession.

Go to Part 4 - The death.

Back to The story of Toni Gobbi: from citizen to mountain guide.