Part 3 - The mountain guide: evolution of a profession

Published on 31/1/2023

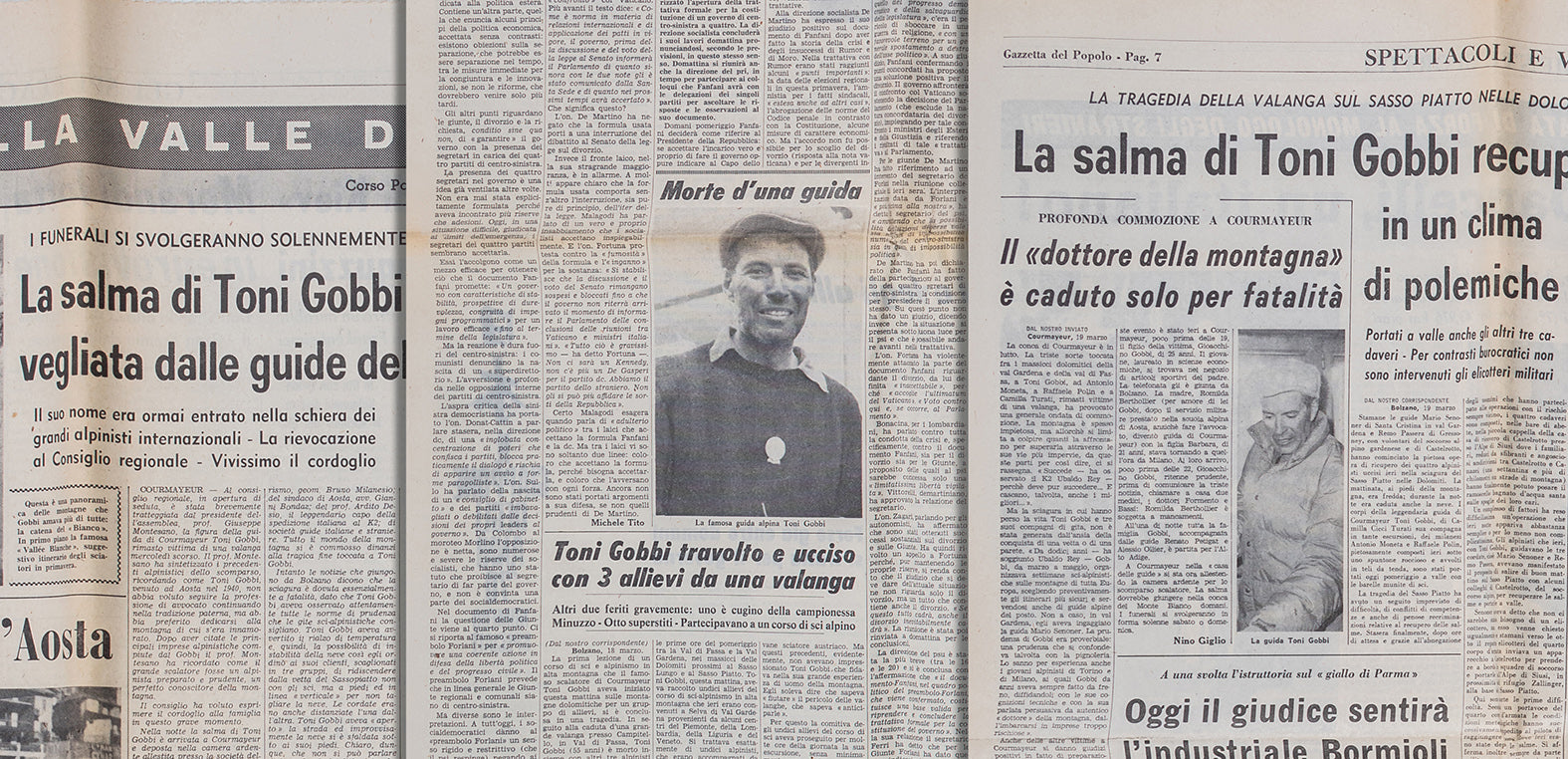

Toni becomes a mountain guide in 1946, fulfilling his dream of transforming his passion for the mountains into a career. He will write to his friend Armando Biancardi: "Now that I'm really a mountain guide, I must always keep in mind that this is my profession and that therefore I have to get out of it at all costs an XY amount of money that will allow me to run my little family for another year, since I don't have fields from which to grow potatoes, apartments to rent to the "lords", woods from which to cut down plants ...".

If he is not the very first, he is certainly one of the first Italian mountain guides from the city. We shall remember that the profession was born between the end of the 18th and the beginning of the 19th century among the villagers who, experts of their places, began to accompany the "tourists of the time" to the mountains. The first mountain guides association in the world is the one of Chamonix (1821), the second is the one of Courmayeur (1850).

After the Second World War, with the first mountain guides from the city, the debate on the opportunity of this opening of the profession ignited. In the assembly of delegates of the CAI (Italian Alpine Club) in November 1947 (in those years the guides were part of the CAI itself), someone even goes so far as to propose excluding from the profession those who were not born and residing in an alpine valley. And it is another of the first Italian guides from the city, Gigi Panei (born in central Italy, a conscript of Toni and also based in Courmayeur), who criticizes this proposal of exclusion in an article in "Lo Scarpone" (CAI newspaper) of January 16th, 1948 "Citizens in mountain guides too", going so far as to argue that mountain guides from the city have now become even stronger than valley guides.

Toni also intervenes on the subject, with an article again in "Lo Scarpone" of June 16th, 1948, entitled "Defending the valley guides". Toni defends the qualities and strength of the guides from the mountains, but agrees with Panei on the possibility of having guides from the city.

His vision of the profession emerges clearly and strongly in his words. "I go so far as to admit (although I do not share this point of view) that a city guide can be allowed to work even without having to be forced to reside in the mountains ... [but] it should be made an indispensable condition - in our regulations - that the citizen who wants to become a mountain guide must undertake to "really be a guide", in short, to exercise the profession because being a guide is a public service and as such it must be regarded and exercised. [...] The aspiration of a citizen who wants to become a guide must not be - in my humble opinion - that of adding a patch to his jacket, but that of embracing and practicing a profession which in his eyes has become so spiritualized to be regarded as a true and proper mission, that is to say, to bring one's fellows to where their technique would not have taken them, but to which, on the other hand, all the aspirations of their feelings tend. [...] In short, yes, even citizens can be mountain guides, but only when they promise themselves to truly be guides, to carry out the activity of guides in all its marvelous and dangerous, terrible and highly poetic aspects. […] Only if we guides from the city truly exercise the profession, only then will we be able to understand our fellow valley dwellers, from whom our ignorance and incomprehension too often distance us.” In fact, throughout his life Toni maintains a profound respect for the mountain people, for their culture and traditions.

The passion for the mountains is central to his approach to the profession. Mario Senoner, one of his main collaborators, recalls: "Toni always told us that we shouldn't be the taxi drivers of the mountains, but we should pass on the passion to the clients!". In an interview with Rai (Italian national television) in July 1963, Toni explains the qualities that a good mountain guide must have: “he must have passion, because without passion one cannot be a guide. Secondly, he must be aware of his profession, that is, he must understand that the client entrusts himself to him and entrusts his life to him. Thirdly, he must have a technical capacity, let's say a technical maturity such as to face any mountain difficulty and especially to face the mountain in any condition".

Precisely this passion and this awareness lead Toni to always feel the responsibility of the client or the group upon himself, and he knows that it is up to him to show the way. His friend Giorgio Bocca would write in an article in "Il Giorno" on 20th March 1970 (two days after Toni's death): "... [he was] in the lead to trace the way, even if a strong young mountaineer was behind: if [the client] had entrusted himself to him, it was up to him to open the way".

With this approach and this vision, Toni concentrates and specializes his activity as a mountain guide on high-level routes, such as the south ridge of the Aiguille Noire du Peuterey, the Hirondelles ridge on the Grandes Jorasses, the Major and Innominata on Mont Blanc. “The kind of climbs I prefer? The big ones. I came and stayed in the Aosta Valley, in the western alps, for this very reason (besides Romilda!).” he writes in a letter to his friend Armando Biancardi.

By creatively fusing his city mentality with mountain culture, Toni becomes an innovator. Enrico Camanni, journalist, writer and mountaineering historian explains: “Toni Gobbi totally renewed the profession of mountain guides. I don't think he had it in mind when he started, but undoubtedly he had the characteristics, the skills, the intelligence and even the personal history to do it. [...] He brought a culture that was not that of a mountaineer, but that of someone born in Pavia, raised in Vicenza, who studied at the university, who saw many things before doing that job, and also saw many other environments, including those of the Dolomites.” First of all, he brings an entrepreneurial approach to his work: the client must be actively sought, not passively waited for, and then developed over time. Not just accompaniment: it must be the guide to propose new experiences. The approach is disruptive in an alpine world where the majority of guides passively waits for the client in the office. Ruggero Pellin, mountain guide and former president of the Courmayeur Mountain Guides Association and cousin of Romilda, recalls Toni's teachings at the guide course: "Go and find the client, don't wait for him to suggest you what to do, you are the one who has to suggest him. And be entrepreneurs of yourselves!”

Toni applies this entrepreneurial mentality to his great intuition which is to try to broaden the guide's work, aiming at all seasons. At that time guiding is a purely summer job that lasts about two months a year, concentrated on mountaineering ascents. Sport climbing and ice climbing do not exist yet, while skiing, for the mountain guides, is very limited. In fact, in the Regulations of the Courmayeur Mountain Guides Association of those years, article 26 reads: "The guides office will be open from the 10th of July to the 30th of September." All the guides hold other jobs for the remaining 10 months of the year. Toni senses the opportunity to expand into ski-mountaineering, a spring activity that can cover the three months from March to June and which can prolong the working capacity up to a more advanced age.

Giorgio Daidola, journalist, writer, historian and ski enthusiast explains: “Skiing arrived in the Alps at the end of the 1800s – beginning of the 1900s from northern Europe. The mechanized lifts didn't exist yet, skiing was a means of mountaineering in the winter, therefore ski-mountaineering! Only in the 1930s, with the first mechanized lifts, downhill skiing developed and eventually became a mass phenomenon. Ski mountaineering then remains a niche, highly concentrated on the mountaineering side, therefore on the ascent, and little on the descent. The practitioners are more "mountaineers" than "skiers". After the war, Toni Gobbi understands the importance that the playful pleasure of descending combined with winter mountaineering in a professional way can have in ski mountaineering, and he understands the scope of long traverses, which link several locations.”

Toni is not the inventor of ski mountaineering, but he is probably the father of professional ski mountaineering and of Italian ski mountaineering in general, as well as a great developer of itineraries and programs never seen before. In those years, a high level of skiing is not required to become a mountain guide (the courses were strengthened in this respect only in the 1970s), and there are few guides who offer ski mountaineering itineraries, mostly for one day.

We must note that in Toni's vision ski mountaineering is at altitude and certainly involves the use of skis but also of ice axes and crampons. Its normal field of action is the mountain above 3000 meters and its purpose is the realization of high-altitude traverses and the conquest of peaks. It starts in mid-March, the slopes are considered too dangerous before that date, and it's a complete activity. In fact, he writes: “a true ski mountaineer is someone who finds the pleasure of ascending, the joy of the summit and the satisfaction of descending. […] We want anyone who does ski mountaineering to do it completely, in all three parts”.

In 1951 he begins to offer to his clients the Haute Route Chamonix-Zermatt (developed by the French and the Swiss in the first part of the 1900s), extending the departure from Courmayeur and the arrival to Cervinia, and thus took shape in him the idea of creating other multi-day ski-mountaineering itineraries, real traverses to explore entire areas and massifs. This is how the "Settimane Sci-Alpinistiche di Alta Montagna” (High Mountain Ski Mountaineering Weeks) are born, with the patronage of the CAI Central Commission for ski mountaineering and, starting from 1961, also of the FISI (Italian federation of winter sports) Ski Mountaineering Commission. Starting from 1954, the "Britannia Week" is also proposed (which touches four 4000m peaks in the Swiss Alps and takes its name from one of the huts touched) and from 1955 also the Bernese Oberland week. In the following years, the programs will be enriched with another 16 itineraries throughout the Alps, all studied with care and attention by Toni, all of great interest for the territories explored and in any case with ascents ranging between four thousand and seven thousand meters per week.

With the exception of 1958 (the year in which he participates in the expedition to Gasherbrum IV), the Weeks will continue uninterruptedly until 1970, the year of his death, occupying him for the 3 months of srping, in which he arrives home on Saturday and leaves again on Sunday : Toni doesn't miss a single one of “his” Weeks, because the boss always has to lead from the front, as he always say.

From 1951 to his death in 1970, Toni guides more than one hundred weeks, and 314 clients complete at least one. 148 (ie almost half of the total) complete at least two, and of these, 49 complete at least 5. In 1966 alone, 94 clients participate in the Weeks! To understand the extent of the phenomenon, one can read the roll of honor of the participants: these are city clients, often professionals or entrepreneurs, mountain lovers but not necessarily mountaineers or climbers, many also foreigners.

With this offer, Toni manages to significantly broaden his customer base. Giacomo Bozzi, son of Irene who was one of the main clients of the Weeks, explains: “What still strikes me about that approach is the ability to bring people, ordinary mountaineers from the city to extremely important results.” According to Giorgio Daidola: "Toni Gobbi was a great trainer, who developed the skills of his ski-mountaineers, creating a highly loyal clientele." Leonardo Lenti was a young client of Toni's in the late 1960s: “he really had the ability to bring together these extremely heterogeneous groups of people, and also somehow to cement them. [...] There were people of profoundly different cultural levels and personalities, whom he managed to amalgamate with his being "the boss", unquestionably the boss. In the end they were all happy, very happy, it was truly a joy. And when everything had gone well he relaxed, and he was no longer the big boss, but everyone's companion."

How does he manage to achieve these results? In the words of Umberto Caprara, notary of Vicenza, client and friend of Toni: "The Weeks are the result of enthusiasm and organisation, of tenacity and planning, of abnegation and study: qualities that can coexist in an exceptional man like Toni, in which mountaineering culture and ability, spirit of sacrifice, will and organizational skills came together in the almost missionary vocation of guiding the greatest number of mountaineers to enjoy the wonderful secrets of the winter in the high mountains.”

In fact, organization is the basis of everything and it is an area in which Toni excels. He thinks of everything and plans everything, from the itinerary to the timetables, from logistics to equipment and food. All of this is rolled out with rigidly enforced strict rules, which everyone must comply with for the success of the Week. Again Lenti: “He was an extremely rigid, hard, severe, attentive person who controlled everything and who clearly knew everything about what was happening around him. He strongly scolded people who didn't behave exactly the way he wanted. [...] He exuded strength, firmness, decision, and at the same time extreme attention to those around him, to the people whose life and health was entrusted to him. He felt responsible for everything and everything and so he obviously tried to control everything.” In the words of Renato Petigax (one of his main collaborators): “The organization was perfect. He even made a list of what customers had to bring in their backpacks, and often before leaving he checked and had the useless weight dropped off.”

Giorgio Peretti was a client of Toni in the 1960s before becoming a mountain guide himself. He remembers the Weeks well: "Toni always walked at a slow and regular pace, always leaving the hut 2-3 hours before the other guides (who often almost made fun of him) to ensure that the group reached the top in ideal conditions for the descent . With this system, unlike other guides, he always brought his group to the end, with very rare exceptions. ”

For the ascent then, in every situation and with any client, the rule is clear: you climb for 50 minutes, you rest for 10. And the track is always that of the boss, as Lenti recalls: “The track both uphill and downhill was a duty strictly his, and everyone had to follow him without delay both uphill and downhill. This is both for safety reasons and not to disturb the aesthetics of the virgin slope. When he got to the bottom he looked at the slope he had skied on, he looked at the track and was clearly satisfied with the beautiful, well done track. ”

The Weeks are therefore a highly successful formula that everyone is very happy with, and which will leave indelible memories in the participants. This is the case for Mrs. Bozzi, for example, remembered in the words of her son Giacomo: "My mother used to tell of these beautiful moments in the midst of wonderful mountains, and then the whole human dimension linked to the great leader of these Weeks and to the people who were close to him ... therefore the guides, Senoner, Petigax, who were all characters of value and weight in any case, and also to the other participants."

The spirit can also be understood from Toni's words in an information brochure, which explains the number of participants: “Registration for each Week is limited to a maximum of 12 participants. This, as well as for understandable safety reasons, also to maintain that character of quiet, elegance, ease of accommodation and provisioning, complete fraternity among the participants which has always been one of the most welcome characteristics of the Weeks and one of the secrets of their success.”

This movement had no equal at the time, as Mario Senoner recalls: "Other guides abroad worked with ski mountaineering, but no one in Europe had such a complete and vast program, which touched so many clients and with so many offers."

The world of the Weeks brings many elements of great innovation to the profession of the mountain guide. In addition to the already mentioned extension of the work during the year, certainly also the offer of complete programs (not just single trips/days) but above all the work away from home, in a world in which the guides were mainly "experts of their territory" and in almost all cases they limited their action to their "home" mountains. Toni takes his clients all over the Alps, and, with great vision, even outside the Alps and Europe. Giorgio Daidola explains: “ski travel is the logical evolution of the Weeks and will be of great influence for those who come after.” In fact, the 1966 Weeks program is enriched with the proposal of the "double ski-mountaineering Week in Caucasus", from the 23rd of June to the 7th of July. It is reserved for ski-mountaineers who have completed at least two weeks and has as its objective, in the midst of the Cold War, the ski-mountaineering ascent of Elbrus (5633m), in the territory of the Soviet Union. There are 12 places available but in the end there will be 13 participants, accompanied by Toni, Renato Petigax and Giorgio Colli as guides. After an acclimatization on Mount Cheget-Tau-Tchana (4109m), on the 1st of July all sixteen expedition members (thirteen clients plus three guides) reach the summit of Elbrus! Toni writes in an article on the expedition: "Elbrus had already been ascended and descended with skis before us, however we believe we were the first ski-mountaineering group to have climbed it in such a significant number and we also believe that it is the first time that women can be proud of having made the ski-mountaineering ascent.” On the way back, not to forget the cultural aspects, the last two days are dedicated to visiting Moscow!

In 1967 the organization pushes even further and offers the "Triple ski mountaineering Week in Greenland", from the 15th of June to the 5th of July, into the Stauning, which offer (as stated in the programme) "a grandiose complex of and undoubtedly profitable ascents for ski mountaineering.” 9 places are available for ski-mountaineers who have completed at least two weeks, and they are all booked. It's a great experience for everyone, in a logistically difficult but fascinating environment. The group completes several ascents including two first ski-mountaineering ascents, a first ascent and two first traverses. In the final report, Toni writes that "Greenland also has mountains of notable ski-mountaineering interest and of great technical satisfaction for complete ski-mountaineers."

In 1969 the "Second Italian ski-mountaineering expedition to Greenland" is planned, from the 15th of June to the 8th of July. There are 7 clients participating. Among them, Leonardo Lenti who is only 24 and still remembers it as "one of the great experiences of my life."

The 1970 program even plans the "Ten-day Ski mountaineering ascent of Damavand (5770m)", in Iran, but unfortunately it will not be made because of Toni's death on the 18th of March.

With today's eyes, we cannot fail to notice a very innovative and absolutely avant-garde approach to "marketing". First, Toni has a full time secretary for his guiding job (not involved in the shop or bookstore). She helps him organize his work, manage clients and organize the Weeks. For the latter, every year he creates a very complete brochure of about fifteen pages for the presentation of the program. It contains the detailed schedule for each week, all the information on enrollment and costs, as well as lots of information in a format that today we would call "FAQ" (e.g. What are the characteristics of the weeks? How do you have to ski? What are the huts like? Who will provide the food?). With a view to promotion and retention, the golden book is always present, with the complete list of participants since the beginning of the project. An initial segmentation of customers is also very interesting (here the data from the 1970 brochure): "20% are young people between 18 and 25 years old, 60% are people between 26 and 49 years old, 20% % are enthusiasts aged between 50 and 65 [...] 18% are female ski mountaineers, 75% have previous ski mountaineering experiences, 25% instead come from piste skiing and are therefore at their first full ski mountaineering experience."

Each client is taken care of personally and Toni writes personalized letters to all of them to address the various offers and programs, with a view to developing skills and increasing difficulties. He also works on loyalty! As early as 1957, the organization awards the Weeks badge to participants who complete the programme. In the following years the badge becomes a pin, with special holes to pin the stamp of each completed week.

It is also interesting to analyze the costs of the Weeks, to discover that they are comparable to those of major mountaineering ascents, but with an activity that lasts a whole week and that has a client-guide ratio of 4-5 to 1.

Let's take 1961 for example: the price of the Haute Route Courmayeur-Chamonix-Zermatt-Breuil is 27,500 liras (the fee includes the organization, the guides and their expenses) to which must be added another 17,500 liras for meals, shelters, transport, for a total of 45,000 liras. The Oberland Week costs 30,500 liras, which become 50,000 if you count everything. It is useful to compare these costs with some climbs offered by the Aosta Valley guides: the Dent du Geant (normal route) costs 16,000 liras, Mont Blanc (from the Gonella hut) 32,000 liras while the Matterhorn (Lion ridge) 38,000 liras. Since 1963, a 15% discount is introduced for young people under 25 years. If we look instead at 1968, we find the Haute Route at 45,500 liras, with a Dent du Geant at 30,000 liras, a Mont Blanc at 55,000 liras and a Matterhorn at 50,000 liras. We note that starting in 1969 the fee for the Weeks also includes accident and civil liability insurance for the participants.

In addition to practice, Toni also works on theory and training.

In 1964, on his initiative and insistence, CAI established the qualification of "Ski-Guide": it can be obtained by guides who are already ski teachers or by guides who attend a special course (the first is in Courmayeur from the 3rd to the 10th of April, 1964). The Ski-Guide badge number 1 is precisely that of Toni, and he will be the one to direct all the courses. We shall remember that in those years skiing is very small in mountain guides courses! The Ski-Guide is thus authorized to organize ski mountaineering technique courses and ski mountaineering activities/programmes.

The world of the Weeks is also consolidated and affirmed through conferences of the participants. The first is in December 1955, in Courmayeur, to "go back to the best moments of our common activity based on the truest and most severe form of ski mountaineering, and make plans for the future" as stated in the invitation. The second convention is in 1956, then in 1958, then in 1960 and finally in 1965, on the 9th and 10th of October. “However, it was about time we all got together: we are by now not only a force in high mountain ski-mountaineering, but we also represent a school, a method, a system, a trend that can and must say something in the field of our favorite activity” reads the invitation. The aim of the conference is the formulation of a "Decalogue for the high mountain ski-mountaineer" in which all the principles of the activity are clearly outlined.

In 1967 he is commissioned by Fabbri Editori to take care of the part relating to ski mountaineering in "The Encyclopaedia of the Skier", helping to make the discipline known to the general public.

Starting in 1967, as part of the Weeks, he creates the "National school of high mountain ski-mountaineering" to better prepare the clients. The school operates in the month of March (the starting period of the Weeks) and also offers, in the summer, "Ice, mixed and mountain rescue courses."

Toni is also a great popularizer of his activity as a guide and mountaineer, holding numerous conferences throughout his career. When he is not in the mountains, he is often busy in his office preparing conferences, as well as studying new itineraries. The topics are varied and he always develops new ones according to the moments and situations.

He starts early, as evidenced by a letter to his brother-in-law Franco Pozzani (husband of his sister Rita) dated 20th April 1951, for the organization of a conference at the CAI in Thiene. Toni writes as follows: "The conference is entitled "Western Alpinism seen by a Dolomites expert" and lasts about 50 minutes, illustrated by slides in black and white and in colour. In this conference I explain the substantial differences between mountaineering in the Dolomites and in the western Alps. It is a conference that I have now successfully held in at least 50 sections of the CAI.”

With the development of his career, the activity of lecturer also extends abroad. In January 1962 he is invited by the English Alpine Club (of which he will be a member from 1965). On the 23rd of January in London and on the 26th in Liverpool he holds a conference titled "A mountaineer who became a guide" in which he tells his personal story, centered on his passion for the mountains.

Toni is also one of the first, if not the first, mountaineer and guide to create specific products for his activity. In fact, already in 1954, in the price list of his " Alpinist and Skier's Shop" of Courmayeur there is a section "Guida (guide) mountaineering equipment", in which he writes: "In this section I have listed all the mountaineering products and tools whose technical features and production have been personally studied and directed by me in collaboration with some of the best Italian manufacturers specialized in mountaineering equipment. These are items that, before putting them up for sale and recommending them, I have tested for several years, so that they can give the most ample guarantees of rationality, resistance and - what is more important - perfect compliance with the needs of modern mountaineering technique, both for the Dolomites and for the western alps. All “Guida” products (registered trademark) are original only if accompanied by the authentication tag bearing the handwritten signature and the progressive serial number."

We find many "Guida” products including high mountain and climbing boots, ski mountaineering boots (in collaboration with Dolomite), Italian hemp rope for mountaineering, windbreakers for mountaineering and ski mountaineering (with Merlet), down jackets, trousers, shirts, mountain sweaters, gloves, … up to bivouac tents.

Toni is not only a very active mountain guide, but also contributes significantly to the growth of the profession and its representation.

First of all, he always makes sure that the guides are properly paid. Senoner recalls: "Toni fought for the rates, he said that the guides must be paid adequate rates." He also harshly criticizes customers who try to underpay. This is how he vents in a letter to his friend Armando Biancardi: “.. the greatest cowardice, Armando, is that those pigs don't do it with me, but they do it with those of the guides who are the least educated. Those filthy people, who studied and grew up in the city, take advantage of the ignorance and difficulty of speaking of those poor fellows.

In 1946, having become a guide, he joins the Courmayeur Mountain Guides Association, and immediately becomes part of the President’s Cabinet. However, he will never accept to become president of the Association, despite being asked several times, in order not to disturb the delicate balance of the village and his excellent relations with the locals.

However, he immediately moves to a higher level: in 1947 he enters the President’s Cabinet of the Aosta Valley Guides Committee (today UVGAM), where he collaborates with Sen. Chabod (then president of the Committee) for the drafting of the regional law 28-9-51 n2 concerning the organization of guides and porters in the Aosta Valley.

In 1951 he joins the teaching staff of the Guide and Porter Courses of the Aosta Valley, of which he becomes Technical Director in the second half of the 1950s.

In 1957 he is appointed President of the Aosta Valley Guides Committee, a position he holds until 1966. In this role, for the centenary of the first ascent of Mont Blanc by the Courmayeur Guides, he organizes and coordinates the first ascent of a RAI television crew to the top of Mont Blanc in the summer of 1963. There he is interviewed and this is broadcasted on the August 13th evening news.

In 1965 he becomes the National President of the CAI Guides and Porters Consortium.

In this area, his greatest intuition is the creation of an international body that brings together the guides of all countries: the IFMGA (International Federation of Mountain Guides Associations. We read in the historical documents of the association: "the idea to unite all the mountain guides of the world in one single family probably grew from the idea of our unforgettable Dr. Toni Gobbi and Bernhard Biner from Zermatt, who had met on the occasion of the centenary of the Courmayeur Mountain Guides Association in 1950.” In the first part of the 1960s, the meetings between the various supporters of the idea (with Toni at the forefront) intensify until 1965, when they meet for the Zermatt mountain guides festival (the centenary of the first ascent of the Matterhorn) and find the conditions to move forward. The foundation of the federation takes place on the 15th of October 1965, involving Italy, France, Austria and Switzerland. Roger Frison Roche (guide and writer from Chamonix) becomes the president and the Swiss Xavier Kalt the secretary-treasurer. Thanks to Toni's contribution, Valle d'Aosta (as UVGAM) still has today its own representation in the IFMGA, in addition to that of Italy. Mario Senoner still remembers having often talked about it with Toni: "In the early '60s Toni told me about the possibility of bringing together all the guides under a single sign, all with the same badge with no more differences among the countries ... come on, maybe we can do it - he told me!" And so it was: today the IFMGA brings together 22 countries and over 6,000 mountain guides from all over the world.

Enrico Camanni concludes: “All this makes Toni Gobbi a new, modern mountain guide. He was a charismatic character who also knew how to tell the trade and make us love it, desire it. With his example he clearly said "I do it like this and it's a beautiful job."

Photo credits: Grivel archive, Gobbi family, Leonardo Lenti, Giorgio Peretti

Oliviero Gobbi. After a degree in physics and a master's in management, he worked for a few years as a strategic consultant in large multinationals before joining Grivel, his family business, of which he is now the owner and CEO. He loves all mountain activities, from mountaineering to ice climbing, from rock climbing to ski mountaineering, which he practices when he can. His favorite Grivel product is the one yet to be invented.

Back to The story of Toni Gobbi: from citizen to mountain guide

Back to Part 1 - The man: from the city to the mountains

Back to Part 2 - The mountaineer: from the Alps to the world

Go to Part 4 - The death.